How the process of layout has changed over the centuries and why we need to rethink it today

By Tobias Köngeter | Posted on 1. 7. 2020 | Updated on 22. 9. 2023

The beginnings of publishing

Essentially, the way information is communicated through printed matter has not changed since the beginning of printing with Johannes Gutenberg around 550 years ago. The density of information back then was much lower than it is today and what little information there was had to be reproduced and made accessible to everyone. The information was put into a format using movable types. It was then reproduced using letterpress printing.

The use of movable lead letters remained the same for centuries, even if machines took over the typesetting in the meantime or even if individual lead letters were cast into lines. The photo set, which only lasted for a short time between around 1950 and 2000, used light and film material, but did not change the fact that information was put into a rigid layout and then reproduced. Desktop publishing digitized the process, or more precisely the tool, because lead, light and film became keyboard and mouse. The procedure remained unchanged.

Change in communication

However, after half a millennium of publishing, the density of information has increased drastically, so that today we speak of information and stimulus overload. Information is no longer relevant to everyone, and it is no longer possible to absorb and process all information. One result of sensory overload is decreasing attention span. In order to make printed information more relevant and also have an additional appeal, individual components began to be replaced. This is not new, because there were already numbering machines in book printing that made printed matter unique, even though it was a reproduction of one and the same piece of information. In doing so, they help every single printed copy out of a total circulation of thousands or tens of thousands to become irrelevant. With the advent of digital printing, addresses and names were also exchanged, because in this printing process there is no longer a rigid information carrier like the lead in letterpress printing, the film in phototypesetting or the printing plate in offset printing. Layouts are provided with placeholders into which an address, a name or even a voucher code is then printed. This is a little more impressive with images than with text, but the placeholder principle is the same. This makes a printed matter a little more personal, but it only appears to be more relevant, because some of the content changes, but basically nothing in the information. That may also be one reason why such personalizations occur were able to attract attention for a few years, but no longer work today. They offer no added value.

In order for printed matter to be relevant and convincing today, it must bundle information and provide the information recipient with exactly the information they need. This could well be an exhibition accompanying volume, in which information is reproduced in a rigid layout by printing. This could also be a postcard in a private person's mailbox that suggests other suitable items based on their last purchase. Or a travel guide with travel tips, events and the like about the exact information that a person left in the online form when booking.

The failure of the layout programs

Of course, such printed matter can no longer be created by simply exchanging parts of the layout or filling placeholders. The more individual and dynamic they are, the more unpredictable the type and amount of content, i.e. text and images, becomes. Conventional layout programs such as Adobe InDesign and QuarkXPress are not suitable for this.

In recent years, Adobe has implemented some functions in InDesign such as data merging and liquid layouts to enable customizations and variants, but basically it's just about filling placeholders. Information can only be completely exchanged to a limited extent and the layout is always the same in the end. If you wanted to create completely custom layouts, you would have to do it by hand. Of course, this cannot be represented economically. But what is design, layout and typesetting all about?

What visualization of information actually means

A design always primarily follows the common visual design laws of harmonies, contrasts, conciseness, proximity, similarity and so on (see also wikipedia.org/wiki/Gestaltpsychologie). Subordinately, design follows the secondary design specifications, for example of a corporate design, which then determines which elements can have which properties. When designing, a designer applies these laws, redefining the laws in new works or adapting them from previous works to the new one. Two examples of such laws are:

- The logo is always at the top right with a size of x and a spacing of y. (Redefinition or Adaptation)

- In the previous work, one image was placed on the left of one page, now two images should be used at this point. They can be placed better next to each other below, but retain the circumferential spacing and size. (adaptation)

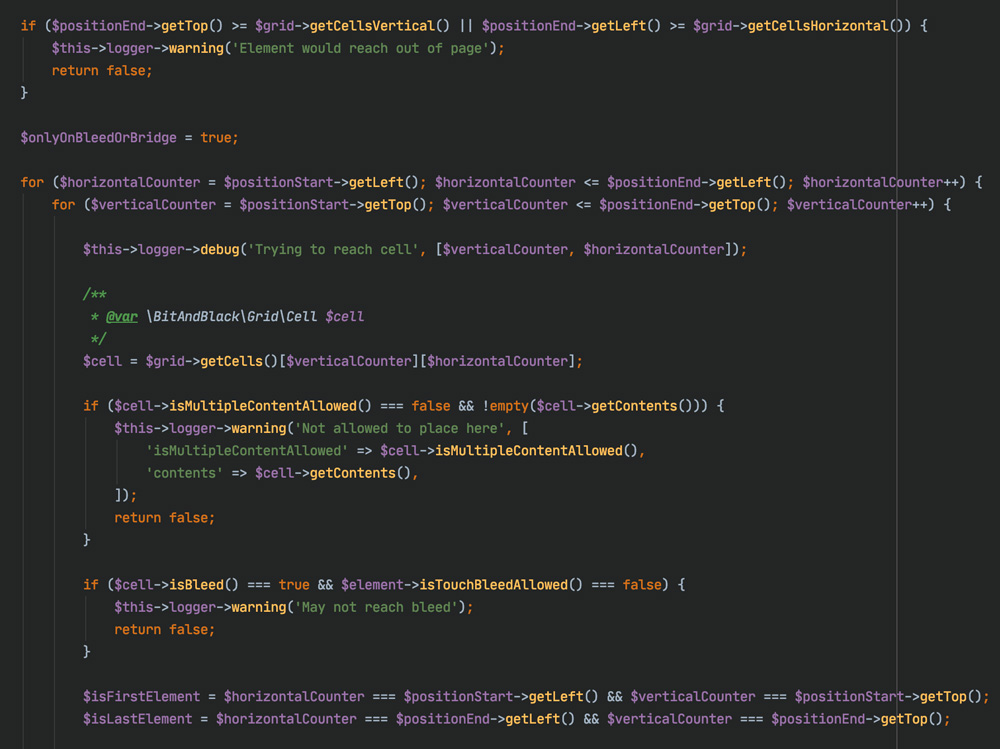

If software were able to understand and apply such laws, it could create layouts in arbitrary variations on its own.

Software can design

This is exactly the type of software we created with ManyPrint Solutions. Here it is possible to define basic design rules, for example the type area, columns, gutters, formats for texts, images, lines, and to create layouts based on these rules. Variants and adaptations that would take a designer hours and days can now be generated in seconds. The use of artificial intelligence is initially not necessary because the design follows comprehensible rules. However, it can be used beforehand when processing information to group, structure and supplement content, and it can be used afterwards if necessary. By evaluating the interactions, the AI could learn which layouts are well received by the recipients and which are not, and thus approach the optimal design step by step. So-called A/B tests are also possible with printed matter. This term comes from web development and describes that individual elements (e.g. a button) are delivered to website visitors in different versions and then it is observed which version is better received. This can also be achieved in printed matter with ManyPrint Solutions.

By using ManyPrint Solutions, layouts for printed matter are now fully digitized — not just their design tools, but the entire manufacturing process. Print is no longer different from digital and is on par with the web. Print has also come to life again, because the information contained in a printed matter can be obtained at the moment it is played out. This means that printed matter is almost “live” — the only delay occurs in the duration of print production.

If print is to remain relevant in the future — or wants to become so again — such dynamic printed matter is essential. At the same time, people will become more and more accustomed to personalized printed products and recognize their advantages. It seems plausible that one day personalized (relevant) printed matter will be preferred over non-personalized (irrelevant) printed matter. Those who can provide relevant information have an advantage.